By Kil-Young Yoo

Silence, absence of sound that is attended while it is voided.

Knowledge has no end. Life has an end. To chase/pursue knowledge, which has no end, with life, which has an end, is dangerous.1

but

Man pursues black on white.2

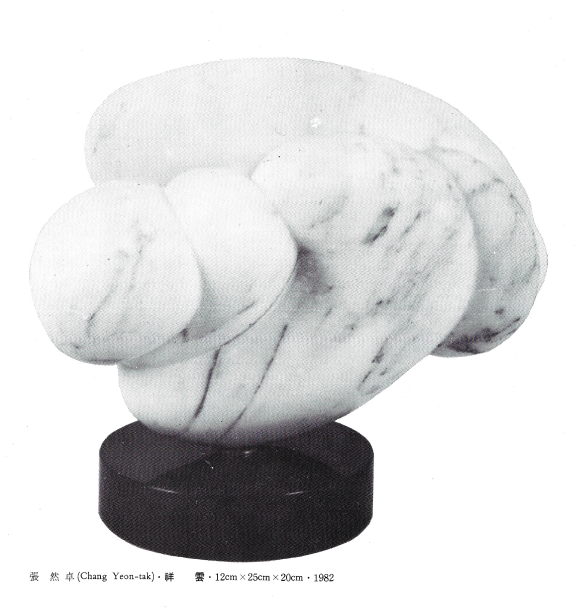

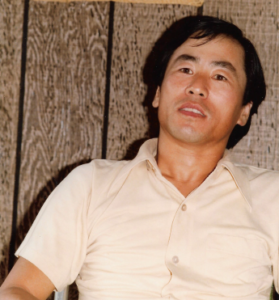

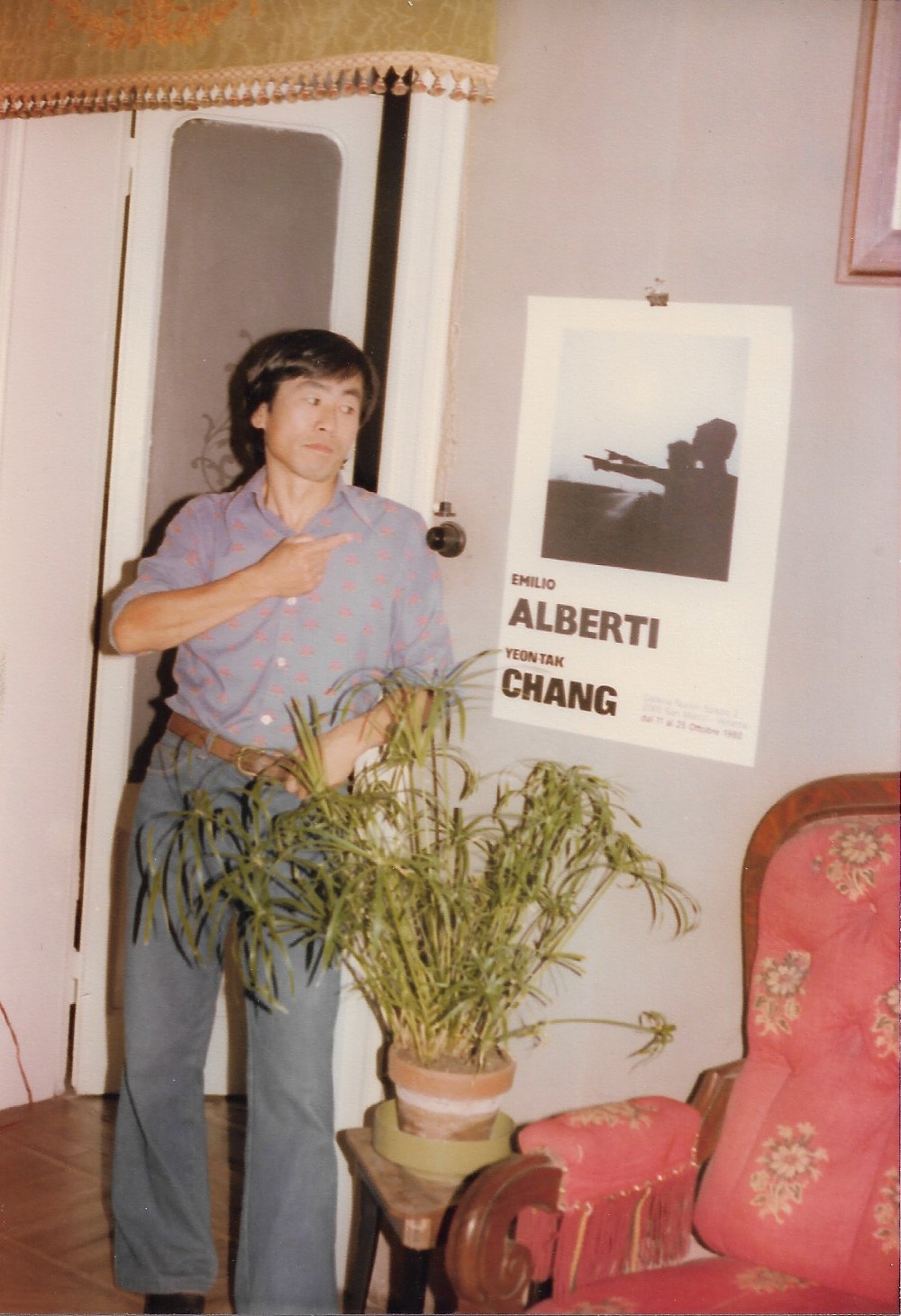

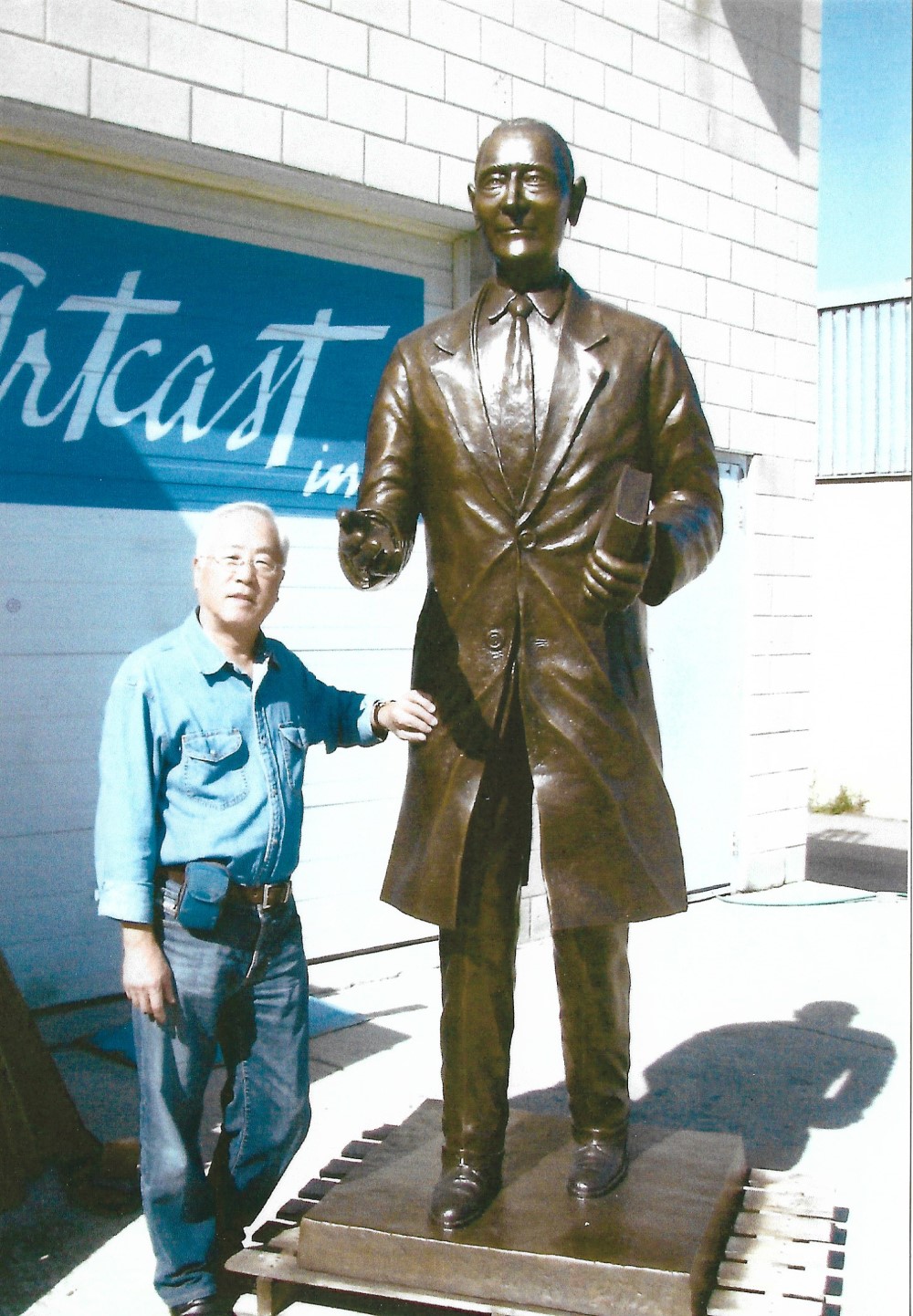

“Arting3” is Yeon-Tak Chang’s endless questioning about his spiritual identity and endless pursuing of the truth occurring in the labour (both mental and physical) of his sculpting. The question and pursuit is his spiritual locus of arting that is the locus of labouring where he kneads with earth and carves with stone.

The direct contact with the stone, as I carve a design, becomes the transitory moment into a continual voyage in unknown space releasing my inner vision.4

The continuous voyage in unknown space seems to me the unknown desire to journey to an unknown destiny that he consciously follows. Perhaps the continuous voyage in unknown space is an endless journey attempting to listen to the silent echo of his spiritual identity.

Chang said in a recent conversation:

I experience the attempt while carving a stone or kneading clay. Carving the stone to make a sculpture is an endless journey to seek my spiritual identity through endless labouring even though I wonder whether it is my destiny; then I imagine, Sisyphus ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight, but the difference between Sisyphus and I is that I am forming my destiny through my labouring, the unknown desire for questioning and seeking my spiritual journey.

Here he suggests that carving the stone through his labouring reveals the state of his arting that is an unknown desire to journey to a mysterious destination for grasping his spiritual identity.

… the world’s worlding cannot be explained by anything else nor can it be fathomed through anything else. This impossibility does not lie in the inability of our human thinking to explain and fathom in this way. Rather, the inexplicable and unfathomable character of the world’s worlding lies in this, that causes and grounds remain unsuitable for the world’s worlding. As soon as human cognition here calls for an explanation, it fails to transcend the world’s nature, and falls short of it. The human will to explain just does not reach to the simpleness of the simple onefold of worlding.5

Then, can’t we explain (the simpleness of the simple) “the unknown desire for questioning and seeking”? Mallarme may help us understand human nature when he states this:

Man pursues black on white.

What Yeon-Tak Chang seems to be interested in and what his arting provokes is to pursue the primordial of pure visual thinking that exists before (or out of) verbal language. The pursuit of the primordial and pure visual world is equally as important as an act of being that occurs in everyday life. This pursuit is based on the primordial image and is a struggle that excludes conceptual speculation. The struggle is expressed and appears as an act of labouring, with the stone and clay as his chosen mediums. The endless act of labouring could let him carve until he gets the smallest particle of the stone which could be smaller than the tip of a chisel. At a certain point he leaves the sculpture as a trace of the primordiality accompanying the pure visual thinking.

The trace leaves a shape which does not resemble anything in the world which appears in front of us, however, the audience can feel the images of wave, wind and an impression of flowing, soaring and growing. What we are confronted with in this situation is the recognition of the existence of the pure visual thinking. The sculptor’s endless act of labouring, as the primordiality of the pure visual thinking, is suggested in his untitled works. He

has no need to close his work off, rather his labour has no limit to possibility.

In a recent conversation with Chang, I discovered that his visual thinking originated in his intuition.

I usually approach carving stone directly without having a sketch or a model for a work. It can be said that I start to carve without any preliminary thought, but it is not to say that I start to a stone with nothing thought out. It is to say that I approach sculpting while emptying myself. It is not to be explicable rationally, but it is certainly understandable; something that comes from my intuition.

These aspects suggest that the purity of the visual thinking as primordiality in his act of arting exists in intuition. Then we could imagine that he could have imagined to make sculpture without labour. But his questing is due to his choice of vocation as a sculptor and from his unknown desire in sculpting as a means of seeking his spiritual identity. The sculpting requires labour. It is important to recognize his will to sculpt. This is another aspect which Chang, the artist, does not need to explicate. It may be called the nature or symptom of his being which, I think, exists with his spiritual identity.

The carving [labouring] is, for me, both an impulsive motion [intuitive act] and a restful peace [freedom]. The restless repetition of the motion is enchanting and helps me discover a mysterious world leading to a spiritual identity.6

The mysterious world here is the trace that he leaves according to his will. What is left is the intuitive vision that is clarified in the dialogue between two ancient Chinese philosophers:

Chuang Tzu and Hui Tzu were strolling along the dam of the Hao River when Chuang Tzu said, “See how the minnows come out and dart around where they please! That’s what fish really enjoy!” Hui Tzu said, “You are not a fish – how do you know what fish enjoy?” Chuang Tzu said, “You’re not I, so how do you know I don’t know what fish enjoy?” Hui Tzu said, “I’m not you, so I certainly don’t know what you know. On the other hand, you’re certainly not a fish – so that still proves you don’t know that fish enjoy!” Chuang Tzu said, “Let’s go back to your original question, please. You asked me how I know what fish enjoy – so you already knew it when you asked the question. I know it by standing here beside the Hao.7

Here Chuang Tzu’s intuition, an imagination, exists before speech. The imagination embraces the intuition which is the creative thinking process. This process is embodied by the intuitive reason and intuitive desire in the thinking process-labour. This embodiment occurs in Yeon-Tak Chang’s arting.

The irony; also the essence, of Chang’s arting is that he attempts to grasp his spiritual identity in the metaphysical state that is invisible, inaudible and unfathomable through the physical state of carving stone and kneading clay which are visible, touchable materials. According to Chang Tzu, Yeon-Tak Chang is in danger because the artist seeks his spiritual identity in the immeasurable through the use of stone and clay; the measurable. Knowledge has no end.

Life has an end. To chase/pursue knowledge, which has no end, with life, which has an end, is dangerous.8 In pursuing this danger, Yeon-Tak Chang aspires to that supreme goal that is the fusion of his intuitive reason with his willful desire. This Fusion is his spiritual identity.

The locus of Yeon-Tak Chang’s arting lies in his freedom and will to voyage into unknown space. This act of labouring in resolving this pure visual thinking is the ‘silent echo’ that he endlessly attempts to grasp.

Endnotes

1. Chuang-Tzu. Chuang-Tzu and Lao-Tzu, trans. Suk-ho Lee, Sam Sung Press, Seoul, 1976, pp9

2. Stephane Mallarme, in Jonathan Culler’s Structuralist Poetics: Structuralism, Linguistics, and the Study of Literature, Cornell University Press, New York, 1975, pp189

3. The author, proposed the use of the word “art” (a noun) as a verb at a panel discussion In Toronto on 18 February 1995, and at a symposium in Sydney (at Goethe-Institute). Australia 23 February 1995

4. Yeon-Tak Chang, from the interview with Anne Tyler, The Independent, Minnesota, USA (October 1983)

5. Martin Heidegger. Poetry, Language, Thought, trans. Albert Hofstadter, Harper & Row Publishers, New York, 1971 , pp 179-180

6. Yeon-Tak Chang, from the interview with Anne Tyler, The Independent, Minnesota, USA (October 1983)

7. Chuang Tzu. CHUANG TZU: Basic Writings, trans. Burton Watson. Columbia University Press, New York and London, 1964, pp110

8. See footnote 1

Kil-young Yoo is an artist and independent curator living in Toronto.